Abstract

The formation of aggregates is a common occurrence during monoclonal antibody (mAb) purification and can happen for several reasons. Aggregates are undesirable due to the possibility of altered pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, and/or increased immunogenicity. Generally, the formation of aggregates is shown to be product or process related. Here we show how on-column aggregate formation is dependent on the resin type and on the resin’s interactions with the mAb loaded. Among the various resins tested, Nuvia™ HR-S Resin, a high-resolution cation exchanger, demonstrated the lowest proportion of on-column aggregate formation with two mAbs. On-column aggregate formation can therefore be minimized by proper resin screening and subsequent optimization of resin type used for purification process development.

Figures

Low Aggregation with Nuvia HR-S

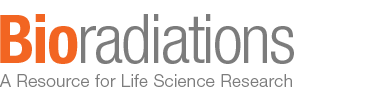

Fig. 1. Nuvia HR-S caused the least amount of on-column aggregate formation of mAb A.

Elution and On-Column Aggregation

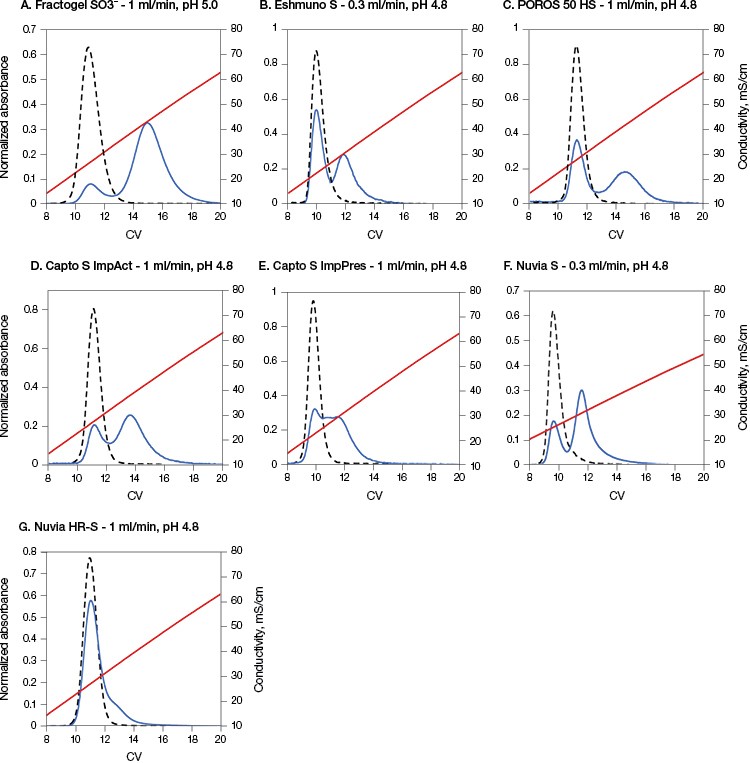

Fig. 2. Comparison of elution behavior and on-column aggregate formation of mAb B.

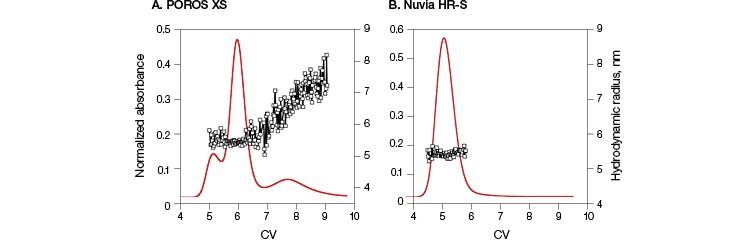

Fig. 3. Comparison of elution profiles on POROS XS and Nuvia HR-S.

Introduction

Aggregate formation can happen due to a variety of reasons, such as self-association of monomers or protein nucleation (Lebendiker and Danieli 2014). Aggregates are highly undesirable in final purified products, especially in therapeutic mAbs. Their presence can lead to different bioactivity and potency profiles, storage stability, and pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties relative to the monomeric versions (Lang et al. 2011).

Because many current-day mAbs have a relatively high pI, cation exchangers are often chosen for removal of aggregates, charge variants, and other impurities in the purification workflow (Shukla et al. 2007, Stein and Kiesewetter 2007). Cation exchange (CEX) purification platforms offer mild processing conditions, which have been thought to induce neither conformational changes nor unfolding during protein binding (Staby et al. 2005).

However, multiple recent studies have reported two-peak behavior during mAb elution from CEX resins, due either to conformational changes in the protein during the binding step (Gillespie et al. 2012) or to reversible self-association of the mAbs at high salt and protein concentrations during the elution step (Luo et al. 2014). Both conformational changes and mAb self-association lead to on-column aggregates. However, the degree of on-column aggregate formation may be resin- and mAb-specific.

To explore this possibility, a series of different CEX resins were analyzed to determine the effects of their individual characteristics on on-column aggregate formation. Results showed that the proportion of on-column aggregate formation depends in part on the different surface extenders, pore sizes, and pore size distributions of the resins used and in part on the interactions between the mAbs and the selected resin’s structures (Guo and Carta 2015, Guo et al. 2016, Reck et al. 2017). This article discusses the results obtained with resins that can be used for process-scale manufacturing of mAbs and the importance of selecting the ideal resin for such purifications. Based on the results obtained, Nuvia HR-S, a strong cation exchanger, emerges as an ideal process resin to minimize the levels of on-column aggregate formation under the tested conditions.

Materials and Methods

Chromatography resins

Fractogel EMD SO3– (M) and Eshmuno S Resins were obtained from EMD Millipore. According to the manufacturer’s literature, both have a polyacrylate backbone grafted with charged polymers or “tentacles” to facilitate binding of proteins. POROS 50 HS and POROS XS Resins were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific. They are based on a cross-linked poly(styrene-divinylbenzene) backbone with a polyhydroxyl surface coating functionalized with sulfopropyl groups.

Capto S ImpAct and Capto S ImpRes Resins were obtained from GE Healthcare. Both are based on a rigid, high-flow agarose matrix modified with dextran surface extenders. Nuvia HR-S and Nuvia S Resins were obtained from Bio-Rad Laboratories. They are based on an acrylamide polymeric backbone functionalized with sulfopropyl groups. Nuvia HR-S does not contain grafted polymers whereas Nuvia S is grafted with polymeric surface extenders. The physical properties of the resins are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Mean particle diameter and charge densities of all resins used.

| Fractogel SO3– (M) | Eshmuno S | POROS 50 HS | POROS XS | Capto S ImpAct | Capto S ImpRes | Nuvia S | Nuvia HR-S | |

| Mean particle diameter, μm | 74a | 85a | 50b | 50b | 50b | 36–44b | 85 ± 15b | 50 ± 10b |

| Charge density, μeq/mlb | 70–110 | 50–100 | 135 | 88–120 | 37–63 | 130–160 | 90–150 | 100–180 |

a Guo and Carta 2015.

b Values obtained from manufacturer literature.

Comparison of on-column aggregate formation on seven resins after different retention times

Resins were packed into 0.5 cm diameter × 5 cm long columns with an actual packed bed volume of 1.00 ± 0.04 ml. Each column was equilibrated with five column volumes (CV) of acetate buffer containing 40 mM Na+ and then loaded with 0.5 ml of 2 mg/ml mAb A in the acetate buffer. After loading, the flow was stopped and the column was held idle for different hold times ranging from 0 to 1,000 min (data shown only for the 0 and 1,000 min hold time). Two CVs of load buffer were then applied followed by a 20 CV gradient to 1 M NaCl in load buffer. All chromatograms were normalized to a total peak area proportional to the amount of protein injected per unit of column volume. This was done in order to account for small differences in actual protein feed concentration and column volumes, thus facilitating comparisons between runs. The default load and elution flow rate was 0.5 ml/min, but flow rates of 0.25 and 1 ml/min were also used.

Calculation of hydrodynamic radii of the eluted species on POROS XS and Nuvia HR-S

All calculations were done as described in Guo et al. 2016.

Monoclonal antibodies

Monoclonal antibody A was a glycosylated IgG2 antibody with a molecular mass of 150 kD and a calculated pI of 8.7 based on its amino acid sequence. Monoclonal antibody B had a molecular mass of 150 kD and a calculated pI of 7.

Results and Discussion

On-column aggregate formation is dependent on the resin type

Monoclonal antibody A was loaded onto columns packed with seven different resins. The load buffers used in these runs were an acetate buffer containing 40 mM Na+ at pH 5.0 for the Fractogel and acetate buffer containing 20 mM Na+ at pH 4.8 for all other resins. An elution flow rate of 0.3 ml/min was used with Eshmuno S and Nuvia S whereas all other columns were operated at an elution flow rate of 1 ml/min. These conditions were selected to provide the best resolution between peaks for the different resins. Antibody was held on the various resins for times ranging from 0 to 1,000 minutes.

As shown in Figure 1, for the conditions chosen, the protein eluted in a single peak on all resins when elution was started immediately after loading and washing the column (0 minute hold time). However, different patterns of elution were seen for each of the resins when employing a 1,000 minute hold time. All resins showed a two-peak elution behavior with the first peaks appearing at the same retention time as the 0 minute hold time runs. The second elution peaks, however, showed different retention times and percentage of total eluted protein for all seven resins. Such late-eluting peaks were previously found to be a mixture of monomers and higher molecular mass species, aggregates, that appeared to be stable over long periods of time (Guo et al. 2014, Guo and Carta 2014). Further studies showed that such two-peak behavior was a result of resin-induced protein conformational changes that occurred gradually and involved the fragment crystallizable (Fc) region of the mAbs (Guo and Carta 2015).

Fig. 1. Nuvia HR-S caused the least amount of on-column aggregate formation of mAb A. The load buffer for all resins from B to G was acetate buffer containing 20 mM Na+ at pH 4.8 and for A was acetate buffer containing 40 mM Na+ at pH 5.0. The elution flow rate was 1 ml/min on all resins except B and F, which had a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min. 0 min hold time, (– –); 1,000 min hold time, (—); conductivity, (—). Data in A–C and F courtesy of Dr. Giorgio Carta.

Nuvia HR-S yielded the least amount of eluted protein in the second peak (~10%) (Table 2). This result is in agreement with previously reported data showing that the “tentacle type” Fractogel displayed strong two-peak elution behavior (Guo et al. 2014, Guo and Carta 2014), whereas only one peak eluted from a macroporous CEX resin without “tentacles” under otherwise identical conditions (Guo and Carta 2015).

The predominant one-peak elution profile of mAb A on Nuvia HR-S appears to be related to the resin’s internal structure. The tested resins (excluding Nuvia HR-S and POROS 50 HS) contain grafted polymers designed to enhance binding capacity. In such cases, binding is not restricted to monolayer coverage, but potentially occurs throughout the grafted polymer layer (Almodóvar et al. 2011, Almodóvar et al. 2012). Therefore, these resins demonstrated a distinct two-peak elution behavior with a relatively large fraction of late-eluting protein.

In contrast, POROS 50 HS does not have grafted polymeric extenders. Despite this, it showed a distinct two-peak separation with a pronounced late-eluting peak. But POROS 50 HS has a bimodal pore size distribution, which includes large “through pores,” about 500 nm in diameter, as well as small pores, about 22 nm in diameter. It is possible that proteins bind in these small pores, similar to the way they bind to a grafted polymer layer, yielding a large second elution peak.

Nuvia HR-S, on the other hand, has an open pore structure without bimodal pores or grafted polymers and shows the least percentage of protein elution in the second peak (Table 2).

Table 2. Percentage of on-column aggregate formed on different resins (protein eluting in 2nd peak after 1,000 min hold time).

| Fractogel SO3– (M) | Eshmuno S | POROS 50 HS | Capto S ImpAct | Capto S ImpRes | Nuvia S | Nuvia HR-S | |

| On-column aggregation, % | 87 | 44 | 51 | 65 | 50 | 73 | 10 |

On-column aggregate formation depends on unique mAb-resin structure interactions

Two-peak elution behavior is also dependent on the inherent stability of the mAb to be purified. Due to differences in stability, different mAbs may show dissimilar behaviors on the same resin under the same conditions. To demonstrate this principle, a second monoclonal antibody, mAb B, with an approximate pI of 7 and MW of 150 kD, was studied. This antibody is similar to the mAb A in size, but differs in its pI. Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) analysis on fresh mAb B confirmed that it contained only the monomeric species (Guo et al. 2016).

Monoclonal antibody B was loaded onto Nuvia HR-S and POROS XS, and its elution profiles after 0 and 30 min hold times were studied. This antibody exhibited a two-peak elution behavior for 0 minute hold times (Guo et al. 2016) and three-peak elution behavior for longer hold times (30 min) on the POROS XS (Figure 2A).In contrast, a single peak was observed even after a 30 minute hold time on Nuvia HR-S (Figure 2B). In-line hydrodynamic radius measurements confirmed that the single elution peak obtained for Nuvia HR-S consisted exclusively of monomeric species with radii of about 5.3 nm. However, with POROS XS, the hydrodynamic radii of the species increased from 5.3 nm (corresponding to the first two elution peaks) to about 7.5 nm, indicating the formation of aggregates.

Both Nuvia HR-S and POROS XS have an average particle size of 50 µm and, hence, similar resolution. Results also indicated similar elution peak widths from both resins. Therefore, the variances in the elution profile at different hold times are not due to any differences between the resolving powers of the two resins. Instead, these elution behaviors are most likely due to the distinct way in which mAb B interacted with the resins’ surfaces and structures.

Fig. 2. Comparison of elution behavior and on-column aggregate formation of mAb B. Columns packed with POROS XS (A) and Nuvia HR‑S (B) with a 30 min hold time followed by a 20 CV 0–1 M NaCl gradient in 40 mM sodium acetate at pH 5. For POROS XS, the first two peaks contain species with hydrodynamic radii of 5.3 nm, consistent with monomeric mAb B, while the third peak shows hydrodynamic radii increasing to about 7.5 nm, corresponding to a dimeric species. For Nuvia HR-S, a single peak with hydrodynamic radii of 5.3 nm indicates the presence of only monomeric species. Hydrodynamic radii ( ![]() ). Data courtesy of Dr. Giorgio Carta.

). Data courtesy of Dr. Giorgio Carta.

Retention time of mAb B monomers depends on resin internal structure

In contrast to the results seen from mAb A, mAb B eluted as a monomer in two peaks at the 0 time point on POROS XS (Figure 1, Guo et al. 2016). Yet mAb B eluted in a single peak on Nuvia HR-S. To explore this behavior further, the two monomer peak fractions from the POROS XS Column were separately dialyzed against the original load buffer and then individually re-injected into either the POROS XS Column or the Nuvia HR-S Column. Re-injecting the fractions from the two peaks into the POROS XS Column resulted in the same two-peak elution behavior as the fresh mAb sample (Figure 3A). In contrast, reloading on the Nuvia HR-S Column led to the same single peak regardless of which POROS XS Resin peak-produced fraction was re-injected (Figure 3B). This confirms that the two primary mAb B elution peaks from POROS XS contained monomers. The POROS XS contains two different pore sizes that bind mAb B with different strengths and at different rates, explaining the two-peak behavior. Nuvia HR-S, which has a uniform pore size, produced a single peak.

Fig. 3. Comparison of elution profiles on POROS XS and Nuvia HR-S. Elution profiles of fresh mAb B sample were overlaid with the results obtained by re-injecting fractions from the POROS XS with 0 min hold time followed by a 20 CV 0–1 M NaCl gradient in 40 mM sodium acetate at pH 5. A, results from POROS XS. B, results from Nuvia HR-S. Conditions were identical for all runs. Fresh mAb sample ( — ); first peak fraction ( – – – ); second peak fraction ( — – — ). Data courtesy of Dr. Giorgio Carta.

Conclusion

Of all the resins tested under the mentioned conditions, Nuvia HR-S, a high-resolution CEX resin, shows minimal formation of on-column aggregates, irrespective of mAb type. Nuvia HR-S also demonstrated single-peak elution behavior after mAb B had been held on the resin for up to 30 minutes. We know this behavior is not due to its particle size because POROS XS, which has the same particle size as Nuvia HR-S, demonstrated a different elution behavior and aggregate formation. Prior studies have also shown that, when compared with another high-resolution agarose-based resin, Nuvia HR-S demonstrated comparable total aggregate removal, but at significantly higher recovery rates (Ng et al. 2014).

These results underscore the importance of screening multiple resins during mAb purification process development, especially for aggregation-prone mAbs, not only to minimize the potential of on-column aggregate formation, but also to optimize recovery. Without this screening, it is difficult to predict the interaction and elution behavior of different mAbs on any given resin.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their appreciation to Jing Guo, Shaojie Zhang, Arch Creasy, and Jason Reck from the University of Virginia for generating the data included in this article.

References

Almodóvar EXP et al. (2011). Protein adsorption and transport in cation exchangers with a rigid backbone matrix with and without polymeric surface extenders. Biotech Prog 27, 1264–1272.

Almodóvar EXP et al. (2012). Multicomponent adsorption of mono-clonal antibodies on macroporous and polymer grafted cation exchangers. J Chrom A 1264, 48–56.

Gillespie R et al. (2012). Cation exchange surface-mediated denaturation of an a glycosylated immunoglobulin(IgG1). J Chrom A 1251, 101–110.

Guo J et al. (2014). Unfolding and aggregation of a glycosylated mono-clonal antibody on a cation exchange column. Part I: Chromatographic elution and batch adsorption behavior. J Chrom A 1356, 117–128.

Guo J and Carta G (2014). Unfolding and aggregation of a glycosylated monoclonal antibody on a cation exchange column. Part II: Protein structure effects by hydrogen deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. J Chrom A 1356, 129–137.

Guo J and Carta G (2015) Unfolding and aggregation of monoclonal antibodies on cation exchange columns: Effects of resin type, load buffer, and protein stability. J Chrom A 1388, 184–194.

Guo J et al. (2016). Surface induced three-peak elution behavior of a monoclonal antibody during cation exchange chromatography. J Chrom A 1474, 85–94.

Lang DA et al. (2011). Aggregates in monoclonal antibody manufacturing processes. Biotech Bioeng 108, 1494–1508.

Lebendiker M and Danieli T (2014). Production of prone-to-aggregate proteins. FEBS Letters 588, 236–246.

Luo H et al. (2014). Effects of salt-induced reversible self-association on the elution behavior of a monoclonal antibody in cation exchange chromatography. J Chrom A 1362, 186–193.

Ng P et al. (2014). Improving aggregate removal from a monoclonal antibody feed stream using high-resolution cation exchange chromatography. Bio-Rad Bulletin 6439.

Reck J et al. (2017). Separation of antibody monomer-dimer mixtures by frontal analysis. J Chrom A 1500, 96–104.

Shukla B et al. (2007). Downstream processing of monoclonal antibodies – application of platform approaches. J Chrom B 848, 28–39.

Stein A and Kiesewetter A (2007). Cation exchange chromatography in antibody purification: pH screening for optimized binding and HCP removal. J Chrom B 848, 151–158.

Staby A et al. (2005). Comparison of chromatographic ion-exchange resins IV. Strong and weak cation-exchange resins and heparin resins, J Chrom A 1069, 65–77.

Capto is a trademark of GE Healthcare. Fractogel and Eshmuno are trademarks of Merck KGaA. POROS is a trademark of Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Giorgio Carta, Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA

Payal Khandelwal and Mark Snyder, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., 6000 James Watson Drive, Hercules, CA