Watch student reactions to the Science Ambassador Program during the 2013 Day of Innovation in Fremont, CA.

In August of 2012, Bio-Rad launched the Science Ambassador program, a corporate responsibility initiative fostering hands-on life science education. The program links interested scientists with interested nearby teachers through a simple website, so that the scientists can visit classrooms to conduct an exciting, one-hour DNA extraction lab. Bio-Rad facilitates these connections and supplies the scientists with free Genes in a Bottle™ DNA kits for up to 36 students per class, as well as easy-to-follow lesson plans.

In under a year’s time, the program has already made significant progress. Nearly 300 scientists and 300 teachers across the U.S. and Canada have signed up. And, in the single most important measure, more than 5,500 students (plus one big city mayor) have had the program’s signature lab experience: an up-close and personal encounter with their own DNA.

Biology Professor

Walters State Community College (Jefferson County, Tennessee)

These numbers, particularly the number of students served, far exceed the initial goals set for the program. The figures are also notable because they reflect the initiative of individuals — the scientists and teachers who make the first connections and then follow through to make the classroom events happen. By design, Bio-Rad plays a supporting role in their effort. So the program’s early success is really a testament to the passion and engagement of these researchers and educators.

If individuals are responsible for driving the Science Ambassador program’s success, individual scientists or teachers can also make a big difference through the program. Such was the case recently in Jefferson County, Tennessee.

Nestled in the foothills of the Great Smoky Mountains in eastern Tennessee, Jefferson County has both the natural beauty and economic challenges that characterize so much of Appalachia. Many of the county’s schools fall under Title 1 of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, with a significant number of students eligible for free or reduced cost lunches. These tight school budgets allow little room for biology lab supplies. However, one asset the schools do have is Lisa Eccles.

A biology professor at nearby Walters State Community College, Eccles was unpacking a Bio-Rad Life Science Education electrophoresis kit for her genetics course in the fall of 2012 when she noticed a flier tucked into the box. “It wasn’t even a flier about the Science Ambassador program,” Eccles recalls. “It was just one sentence on this other flier that had come with the kit.”

With only this one sentence to go on — the program was then in its earliest pilot stage — Eccles nonetheless soon found the website and signed up as a Science Ambassador. “I’m always throwing leftover models and biology supplies in my van and taking them to the local schools,” she says. As someone who’s used to being involved, she jumped on the new opportunity to conduct the hands-on DNA extraction lab.

Eccles realized that no one else in her area knew about the program, so she did all she could to spread the word to to other scientists she knew, to the new STEM coordinator in their district, and to teachers at Jefferson Middle School, where her daughters were students. At first, teachers didn’t believe that Bio-Rad would provide the DNA kits free of charge. “The amount of money they have to spend on science supplies is almost nonexistent,” says Eccles. “So they were afraid there would be some cost involved.”

Along with scarce funds for labs, having to “teach to the test” or face further funding cuts amounted to another strike against hands-on science learning. “It’s not the teachers’ fault,” says Eccles. “They are trying to cover all this material that the state mandates, so there’s a tension between ‘am I going to cover all this material or am I going to make science cool?’” Given such restrictions, teachers in Jefferson County Schools, as in many schools across the country, often fall back on teaching science mainly through lectures and textbooks.

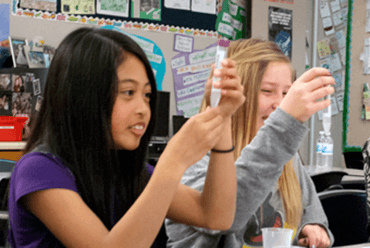

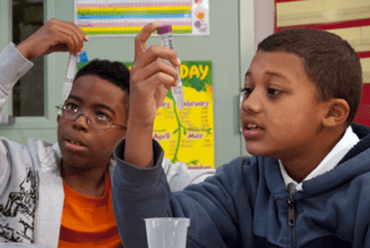

Students watch as their own DNA begins to precipitate in vials. The opportunity to see their own genetic material makes it tangible, rather than an abstract image in a textbook.

However, many of the teachers Eccles knew wished they could have more science labs, and so, once they better understood the Science Ambassador program, they were excited by the classroom experience it offered. Eccles soon found herself booked for two full days of DNA extraction labs at Jefferson Middle School, covering about half of all sixth grade science classes and half of seventh grade classes.

Eccles sees middle school as a key time for kids deciding whether or not they like science. “Fourth, fifth grade? There’s lots of interest in science and they think it’s cool,” she says. “But by the time they are in high school, they’ve decided that science isn’t cool. It’s hard and it’s boring.” She sees this disengagement in many of her college students. Dealing with this in her own teaching gave Eccles an additional, “self-interested” reason to do the labs: the need to intervene with her future students and possibly repair the damage before it happened.

On the day she taught, Eccles didn’t have to look hard among the students to find the “science is boring” stance already taking root. “This is middle school, they’ll just tell it like it is,” she says. “They came in the classroom saying very plainly, ‘I don’t like science.’” However, Eccles also noticed this attitude began to change as the DNA extraction lab progressed, with the students gathering their own cheek cells into test tubes, lysing the cells, and then precipitating out the DNA.

“[As the DNA began to precipitate], I said, ‘OK, now watch,’” Eccles recalls. “And then when they started to see it…it was just amazing when they first saw their own DNA. Up to this point their DNA was just some unknown, itty-bitty thing that they read about.” As the DNA materialized, Eccles found students’ also began asking questions in earnest. Is DNA in all living things? How did they get it from their cells? In each of her lab sessions, she ended up with more questions than she could answer, though she was glad to leave the teachers with much to talk about.

“It was exhausting, but it was a good exhaustion,” says Eccles of the day.

Reflecting on what the students got from the lab, Eccles notes the immediate physical connection they made with their own DNA. However, she also points to another lesson from this experiment: in learning about DNA from a working scientist, the students discovered that there’s a lot researchers still don’t know about our genetic material. “That’s the science part, trying to figure out the rest of it,” Eccles emphasizes, a point that goes against the assumption, built into “teaching to the test,” that any question has a preexisting correct answer.

Eccles’ own interest in science grew from an open question. When she was in fourth grade, she ran over a rosebush while mowing the family lawn. “I actually did some grafting, though I didn’t know it was grafting. I just didn’t want to get caught running over the rosebush,” she recounts. “I didn’t do it well. I used different pieces from different plants, but it grew! I turned that — why it grew — into my first science fair project with my teacher’s help.” She cites having a school and community that supported science — she grew up in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, so science was “normal” there because of the National Laboratory — as crucial to her learning from her mistake and further developing her interest.

“Teachers told me what I did was cool. I made a mistake, but I learned something from it,” Eccles says. “And that’s actually how a lot of the big genetic discoveries were made, rather than having a perfect plan from the get-go.”

Eccles sees many practical advantages stemming from her work as a Bio-Rad Science Ambassador. Students become comfortable with basic lab skills such as pipetting or measuring with a meniscus. Teachers find out that they and students can handle a challenging experiment, and see the excitement it inspires.

Eccles also has noticed tangible, positive results from her visits. She sees parents at games who tell her how interested their children have become in science since the labs. In another positive sign, the experiments also appear to have boosted end-of-year test scores. She describes how “one of my partner teachers recently told me that, for her most recent TCAP [Tennessee Comprehensive Assessment] scores, one of the highest scoring areas was genetics, and that’s usually one of the lowest scoring areas.”

For all this, Eccles feels her role as a Science Ambassador centers on providing the same affirmation she received as a young person interested in science. “Neither of my parents went to college, but it doesn’t matter what your background is; anybody can do science,” she says. “You just need someone to help define your interest and say, ‘yeah, you can do this.’ This can be the key to these students doing great things later on.”

Scientists in all 50 U.S. states and Canada are currently eligible to participate in the program. To learn more, visit the Science Ambassador program website at www.bio-rad.com/scienceambassadors.